Thyroid in pregnancy

Pregnancy and thyroid medications

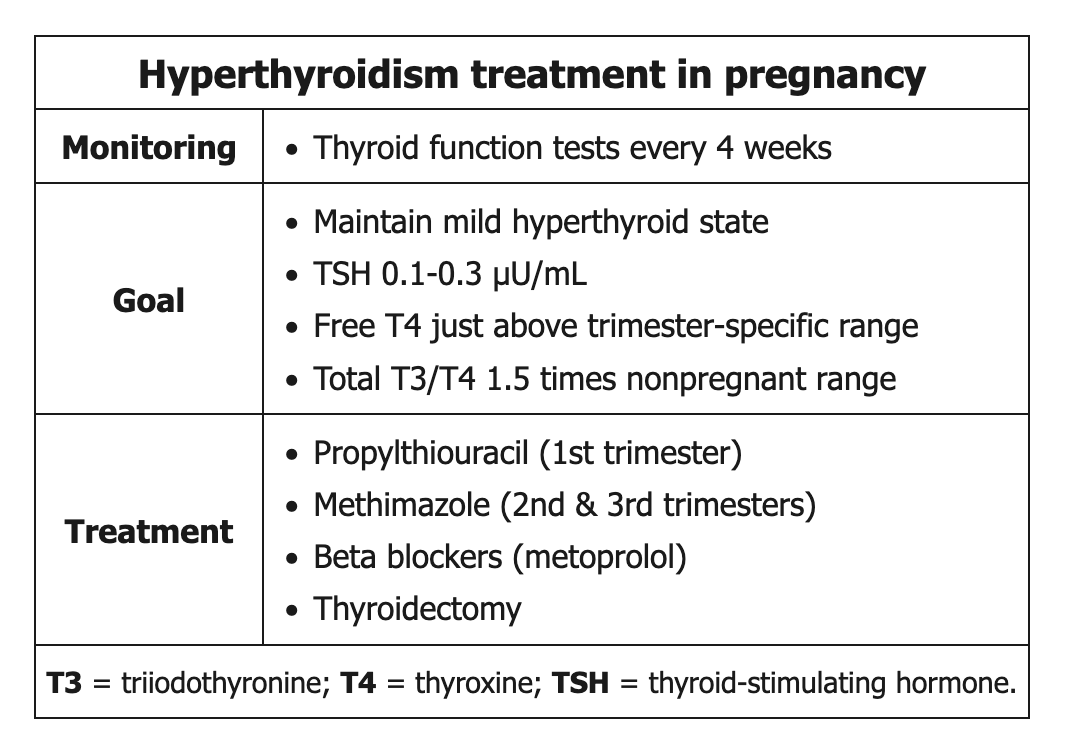

However, methimazole is a potential teratogen and should not be used during the first trimester. These teratogenic effects consist of scalp defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, and choanal atresia. During the first trimester, pregnant patients should be switched to propylthiouracil, which carries less risk of birth defects. For the second and third trimesters, patients are often switched back to methimazole because propylthiouracil carries a risk of liver failure. Beta-blockers can be given if a pregnant patient has symptoms of hyperthyroidism despite the use of thionamide medications, although an attempt should be made to avoid beta-blockers since they can potentially result in harmful effects on the fetus.

During the first trimester of pregnancy, β-hCG stimulation of the thyroid gland causes transient hyperthyroidism. To mimic this physiology and avoid fetal hypothyroidism, the goal of hyperthyroidism management during pregnancy is maintenance of a mildly hyperthyroid state; patients with hyperthyroidism are monitored closely with thyroid function tests every 4 weeks.

During the first trimester of pregnancy, β-hCG stimulation of the thyroid gland causes transient hyperthyroidism. To mimic this physiology and avoid fetal hypothyroidism, the goal of hyperthyroidism management during pregnancy is maintenance of a mildly hyperthyroid state; patients with hyperthyroidism are monitored closely with thyroid function tests every 4 weeks.

Subclinical hyperthyroidism

In patients with normal thyroid function, the net effect can resemble subclinical hyperthyroidism with increased total T4, normal (or mildly elevated) free T4, and suppressed TSH. This patient is clinically euthyroid, with a physiologic increase in total T4 and decrease in TSH. Although she has nonspecific symptoms (eg, nausea, anxiety), her vital signs and thyroid examination are normal, with no evidence of lid lag (seen in most cases of hyperthyroidism) or proptosis (seen with Graves disease). No additional workup is necessary at this time.

Management of hyperthyroidism during pregnancy can be challenging as physiologic changes in the thyroid axis can resemble mild thyrotoxicosis, with:

- Increased total T4

- High-normal or mildly elevated free T4

- Suppressed TSH

The interpretation of thyroid hormone and TSH levels should be based on pregnancy-specific reference ranges (normal total T3 and T4 can be approximated by 1.5 x nonpregnant reference ranges).

Overtreatment of hyperthyroidism during pregnancy can lead to fetal hypothyroidism and goiter, so treatment should be titrated to maintain a mild hyperthyroid state. This patient's test results are appropriate for hyperthyroidism in pregnancy, and her current therapy should be continued without any dose adjustments.

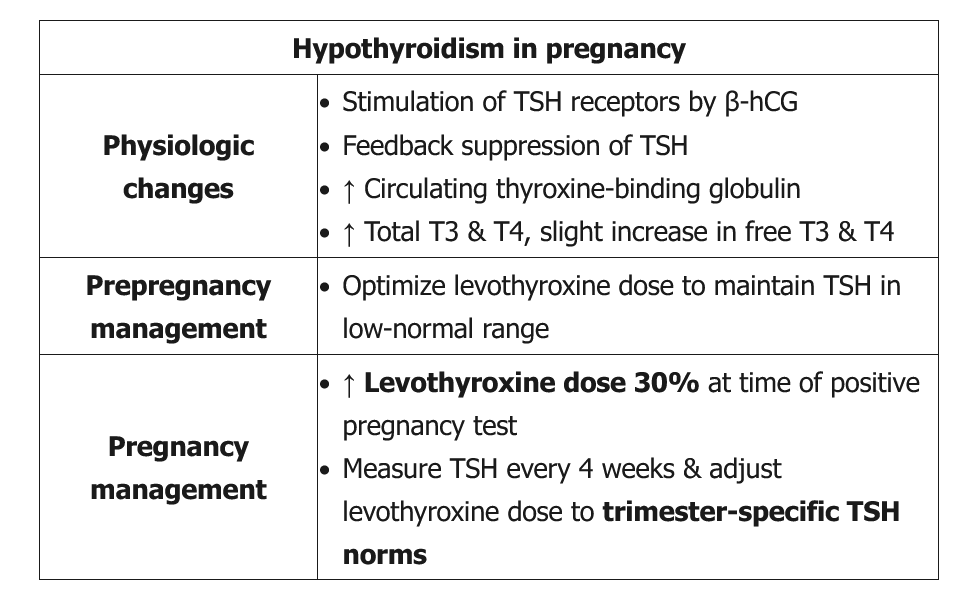

Hypothyroidism and pregnancy

- in euthyroid women: T4 pool increases 40-50% by increased TSH and HCG

- in pregnant women with hypothyroidism, cannot increase own production

- T4 requirements begin increase week 4-6

- empirically increase dosing by 30% when pregnancy confirmed

- measure TSH every 4 weeks first half of pregnancy and around 30 weeks gestation

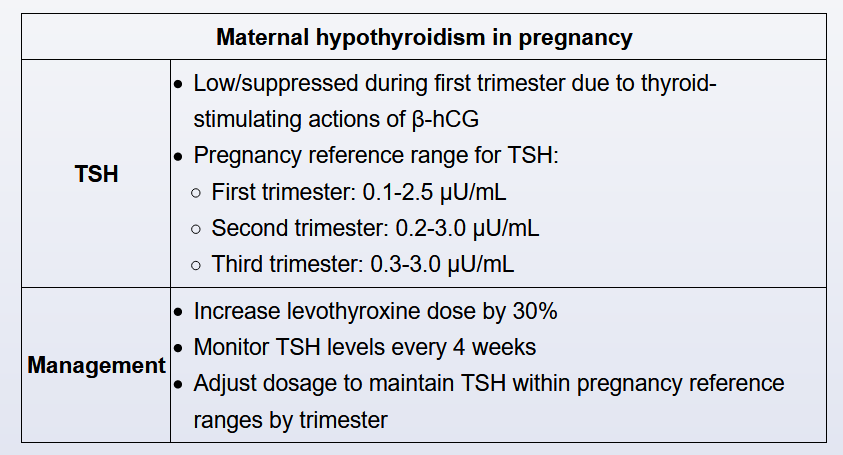

Thyroid hormone requirements increase during pregnancy due to increased metabolic demands. Concurrently, higher estrogen levels cause an increase in thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG). Patients with normal thyroid function can increase thyroid hormone production to saturate the increased number of thyroid hormone–binding sites on TBG, but patients with primary hypothyroidism are unable to increase thyroid hormone production. As a result, patients with primary hypothyroidism on levothyroxine therapy require an increase of about 25%-50% over their pre-pregnancy dose.

Current guidelines advise that the dose of levothyroxine should be empirically increased by approximately 30% (eg, 2 additional levothyroxine doses weekly) at the time pregnancy is first detected. Subsequently, TSH should be measured every 4 weeks and the dose adjusted to maintain TSH within trimester-specific norms (which are typically lower than nonpregnant reference ranges). Undertreated hypothyroidism increases the risk for maternal (eg, preeclampsia, placental abruption) and fetal (eg, preterm birth, fetal death) complications.

T3 is made primarily by conversion from T4 in the peripheral tissues, and circulating levels in hypothyroid patients correlate poorly with thyroid status. If assessment of thyroid hormone is needed during pregnancy, free T4 (using trimester-specific norms) or total T4 can be measured. However, the dose of levothyroxine should be increased first, and TSH is usually adequate for monitoring of thyroid status.